By Anthony P. Pennino (apennino@stevens.edu)

On September 8, 1966, Battle of Algiers, directed by Gillo Pontecorvo, premiered in Italy. Twelve days later, the film was first shown in the United States. The work was received with great acclaim, but it was also greeted with condemnation. It won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival and was nominated for a number of Academy Awards including Best Foreign Film. Nonetheless, it was banned in France for its all too sympathetic portrayal of the FLN. Today, the film is listed as #120 on Empire Magazine’s list of 500 greatest films of all time.Its importance in the history of film is without question. The film excites the popular imagination more perhaps for the legends that have grown up around it -- such as having been screened by the Black Panthers and the Provisional IRA as well as by military and civilian officials of the Pentagon (following a declaration of “mission accomplished” in Iraq) -- than for its actual content. Let us make no mistake: the film is brutal, incendiary, brilliant. Employing a cinema vérité style and a cast consisting almost entirely of non-professional actors, Battle of Algiers depicts the French colonizers and the FLN as equally vicious combatants in the struggle for control over Algeria. And that may be the work’s most troubling feature: the balance inwhich it presents the two sides.

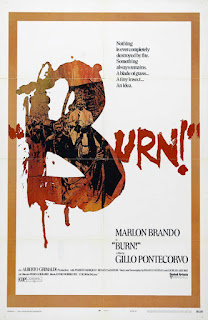

This stunning work of agitprop would stand as Pontecorvo’s final word on the subject of colonialism, except that it isn’t. Three years later, Pontecorvo completed another film on the same subject: Burn! (also known as Queimada); to eliminate some confusion, I will refer to the film by its English title to distinguish it from the island setting: Queimada. Though this film stars Marlon Brando, Burn! has not enjoyed the same reputation as Battle of Algiers.However, Pontecorvo’s examination, depiction, and, ultimately, condemnation of colonialism in the later work is more pronounced and more profound than in Battle of Algiers because he so carefully delineates the different strains of European expansionist behavior. I submit to you, therefore, that Burn! – despite, or even perhaps because of its flaw – is equally deserving of our admiration as a vital piece of emergent political cinema.

Briefly, Burn! is set on the fictional island of Queimada. It has been colonized by the Portuguese, who originally used the indigenous population as slaves. When those slavesrevolted, the colonizers implemented a scorched-earth policy and burned the island’s vegetation killing that indigenous population. Slaves were then brought from Africa to work the sugar fields. The film begins in the 1830’s when Sir William Walker, an agent of the British Navy, arrives to serve as an advisor to instigate a revolution against the Portuguese. He finds the mulatto population, led by Terry Sanchez (Italian actor Renato Salvatori in blackface), ill equipped for the task. Instead, he elicits the aid of poor illiterate slave Jose Dolores (as is Pontecorvo’s habit, non-actor Evaristo Marquez was hired for the role). Between Dolores’ military pressure out in the countryside and Sanchez’s conspiracy in the capital, the Portuguese are overthrown. Walker convinces Dolores that Sanchez is the more capable administrator and leaves the island with the latter in charge of the government. Ten years pass. It is 1848, a date with obvious political significance. Walker, now a representative of the Royal Sugar Company, returns to Queimada to suppress a revolt led by Dolores against Sanchez. Walker has Sanchez killed by his own military and hunts down Dolores, who is also executed. Walker is assassinated as he prepares to return home. Queimada may now be firmly under British control, but the revolution lives on.

It should come as no surprise that Burn! was not initially well-received by the critical press. An illustrative review from the time of the film’s release (1970 in the United States) belongs to Stanley Kaufmann writing for The New Republic: “No such importance (however your view it) is likely to attach to Pontecorvo’s new film Burn!, although it was clearly bucking to be another revolutionary hymn. It was carelessly made and has evidently been shoved and jostled in its final editing. The result is that its spine is broken in several places, and it can only wobble lamely to a revolutionary stance.” i Kaufmann is correct that there were production problems during and after filming – the specifics of which I will focus upon shortly -- but theknowledge that there were production and post-production factors beyond Pontecorvo’s control do not prevent the critic from concluding: “I had some reservations about The Battle of Algiers in terms of its fundamental purpose, but it was so brilliantly made. Such questions can’t arise about Burn! because it is so badly made.” ii

Pauline Kael, long-time critic for The New Yorker, was in the minority back in 1970. She deemed the film “luxuriant” and an “ecstatic epic”. iii Kael also correctly pointed to some of the production’s trouble: “[Burn!] might have reached a much wider audience if the Spanish government, sensitive about Spaniards being cast as heavies, hadn’t applied economic pressure against the production, United Artists. So parts of this picture were deleted and others reshot, and the Spaniards, who had traditionally dominated the Antilles, were replaced by the Portuguese, who hadn’t but aren’t a big movie market. After these delays the picture was given a nervous, half-hearted release.” iv Part of that nervousness was a result of releasing a film with clear anti-colonial sentiments to a public weary of the Vietnam War; Hollywood in general had difficulties addressing issues concerning the Vietnam War during the time of the war and, in fact, while Burn! was in production Warner Brothers released the pro-war John Wayne vehicle The Green Berets. Added to that, the temperamental star and temperamental director had a very public feud which Brando himself described as “Homeric”. v The production troubles and the made-for-tabloid fights provided critics with cover. Kaufmann takes on the role of Gertrude in Act IV of Hamlet; there is no need to listen to the truth of the message because somehow the messenger is flawed.

But when all is said and done Burn! is a work of subversive art. There should be no surprise in saying this. But it is subversive in three distinct respects. First, it is politically subversive. Pontecorvo and his screenwriting collaborator Franco Solinas – who also worked on Battle of Algiers – held Frantz Fanon, and in particular The Wretched of the Earth, in high esteem; they deployed Fanonian ideals in creating both Battle of Algiers and Burn! And as such,it initially appears that Kaufmann might indeed be right. If Burn! merely walks in the shadow of Battle of Algiers, what need do we have for it at all? But there is need for it because its ambitions are that much greater than Battle of Algiers. Burn! not only challenges traditional colonial hegemony but neo-imperialist strategies as well.

Secondly, it is subversive historically. Battle of Algiers is placed in a very clear historical context. That film holds up a mirror to the nation of the Enlightenment, of the French Revolution, of the bourgeois revolution and finds it wanting, hypocritical; the inheritors of that bourgeois revolution are shown denying self-determination to those fighting an anti-colonialrevolution. And while the film is clearly a warning to all colonial regimes, those not directly associated with the Union francaise can feel a measure of safety and distance from its proceedings. Burn!, however, has a muddied historical context. And, as such, it casts a much wider net. It is much more difficult for an audience of the metropolitan center watching Burn! to build a wall between itself and this work even if its nation is not explicitly named in the film.There is no safety in distance here.

Finally, Burn! is stylistically subversive as it utilizes certain Hollywood tropes and formulas to misdirect its audience as to the true nature of Brando’s character Sir William Walker, his fate, and the inevitable conclusion of the piece. An American audience, in particular, must then consider a reexamination of the cultural contexts in which it receives films of the action-adventure genre. Stylistically, historically, and politically subversive – I will peel back each layer of the onion one at at time. As a film’s form is the most readily accessible, I will begin with an examination of its stylistic subversion.

In her review, Kael writes, “It is an attempt to plant an insurrectionary fuse within a swashbuckler – to use a popular costume-adventure form to arouse black revolutionary passions.” vi Kael is exactly right. On the surface, there are many elements that suggest that Burn! is a swashbuckler, a version of Errol Flynn’s Robin Hood with the island Queimada substituting for Sherwood Forest, or, in others words, another people’s revolt against oppression played for heroics, adventure, and the occasional laugh. Shot in lush color with a sense of the epic – including a large cast to portray three armies: Portuguese, British, and Jose Dolores’ rebels – Burn! has the visual quality of the action-adventure picture of the time. Add in the casting of Marlon Brando in the lead. Brando was not yet well-known for his political positions. His refusal to accept an Oscar is still a couple of years in the future. Indeed, he had recently starred in the 1962 version of Mutiny on the Bounty, a piece of imperial fluff with British characters in conflict over a watered-down version of the rights of man while another set of native islanders basically serves as background scenery. And, initially, his character appears heroic in the Errol Flynn mode. He is on the island to ferment revolution. He is working with/for Teddy Sanchez, a seemingly idealistic character. It is only when Brando’s Walker addresses Sanchez and his colleagues after Dolores’ revolt has spread does the audience first fully realize Walker’s intentions.

Another possible point of confusion for the audience is one of the film’s producers: Alberto Grimaldi. At first glance, this does not seem to be a logical collaboration. Grimaldi was best known at the time for his role in producing the so-called spaghetti westerns, particularly the ones directed by Sergio Leone. These films were by the standards of the day exceedingly violent but also hugely popular (making a star out of then conservative actor Clint Eastwood in the process). And though of course belonging to the Western genre, the spaghetti westerns were also extraordinarily critical of the traditional American Western. Leone deconstructs the thematic values of the genre through a Marxist lens and concludes that the West was built by men solely seeking profit as opposed to possessing a desire in building a continuation of Western civilization and furthering the Enlightenment Experiment. Indeed, one only need recall the final scene of For a Few Dollars More when Eastwood’s bounty hunter character Monco is piling the corpses of the bandits he has just help kill onto a wagon and cataloguing them not by name but by the value of their bounty. Grimaldi and his colleagues – including composer Ennio Morricone who had long-standing working relationships with both Pontecorvo and Leone – were practiced in taking the forms of American popular entertainment and re-conceiving them with a subversive or revolutionary agenda. Burn! fits that model accordingly.

Pontecorvo goes a step further by denying the audience the catharsis of violence. When Walker and Dolores are on the run from the Portuguese military after robbing the bank, they find themselves on a small village on the coast. They could flee, but Dolores instead decides to arm the villagers and meet the oncoming soldiers with force. The audience is prepared for a climatic showdown where our heroes defeat the forces of oppression. But Pontecorvo cuts to a point after the victory when the villagers are celebrating and holding the soldiers’ weapons aloft. The audience here is cast adrift, deprived of the traditional story structures of the action-adventure. It must now consider the repercussions of revolution rather than the more entertaining aspects of violent conflict between two opposing forces. We are asked to side with the Dolores’ nascent insurrection not because of emotional investment in the individual but purely because of ideological considerations.

The politically subversive elements of Burn! is our next layer of the onion. So much of the script is concerned with revolutionary and counter-revolutionary dialectic that the piece more often resembles a seminar on anti-colonial insurgency than a work of dramatic realism. I have already discussed the importance of Fanon to the works of Pontecorvo and Solinas, and Fanon’s theoretical concerns have provided the thematic foundation of Battle of Algiers. Carlo Celli in his study of Pontecorvo also provides ample discourse on the importance of Fanon in the development of this film.

Celli demonstrates penetrating insight when he discusses the relevance of the character of Teddy Sanchez, the mulatto puppet president after the first revolution on Quiemada. Celli writes, “Throughout the film Sanchez is portrayed as a weak and ineffectual figure who has the trust of neither the white commercial overlords nor the island’s black, ex-slave population. The sense of an unbreachable barrier between the races and of the impossibility of dialogue is evident in the narrative devaluation of Sanchez…. The gentrified, multiracial Sanchez is, of course, compromised by his association with the moneyed interests of the island. But Sanchez is also presented as a figure who provokes the open disdain and disrespect of both protagonists, Walker and Dolores.”vii The clear polarity of The Battle of Algiers eludes us here. Pontecorvo dangles the possibility of what Graham Greene’s The Quiet American character Pyle would call “the third-way” – a bourgeois revolution – but then removes that hope quickly. That revolution is too obviously manipulated by Walker. The effect here is to eliminate a political option well within an American audience’s comfort zone and increase its sense of unease and perhaps even dread. Edward Said argues, “Thus official bourgeois nationalists simply drop into the narrative pattern of the Europeans, hoping to become mimic men, in Naipaul’s phrase, mere native correspondences of their imperial masters.” viii Here, the third way (the bourgeois revolution) is no way at all, rather a nationalist movement co-opted by a competing imperial power.

Celli also provides cogent analysis of Sanchez’s assassination of the Portuguese governor (wherein Walker has to hold his arm so that he can fire the pistol). Celli notes that the assassination occurs during Carnival, a period where historical hierarchies are temporarily and ritualistically upended. Sanchez heads a new government, a move that has all the trappings of a Carnival atmosphere recast in shades of the grotesque; he clearly does not have a mandate to rule. ix

Nonetheless, Celli misses a key element of the assassination. Fanon states in The Wretched of the Earth: “The appearance of the settler has meant in the terms of syncretism the death of the aboriginal society, cultural lethargy, and the petrification of individuals. For the native, life can only spring up again out of the rotting corpse of the settler.”x The governor’s corpse and the settler’s corpse are one and the same. And with his death, the life of the slave population seems to emerge anew, however temporarily.

In one of the most famous monologues from the film, Brando’s Walker addresses Sanchez and his colleagues as they plan their revolution: “Gentlemen, let me ask you a question. Now, my metaphor may seem a trifle impertinent, but I think it's very much to the point. Which do you prefer - or should I say, which do you find more convenient - a wife, or one of these mulatto girls? No, no, please don't misunderstand: I am talking strictly in terms of economics. What is the cost of the product? What is the product yield? The product, in this case, being love -uh, purely physical love, since sentiments obviously play no part in economics.” xi Walker goes on at length to specify the difference in prices between a wife and a prostitute. He then concludes, “Which, gentlemen, is more important - and more convenient: a slave or a paid worker?” xii The plantation of Queimada has been the location of the battle between colonizer and colonized. Michael T. Martin interprets this speech as representative of the shifting balance in economic forces from mercantile colonialism to open market capitalism “while invoking Enlightenment principles against a competing, although declining, hegemonic state (Portugal) on behalf of an ascending one (England).” xiii In Martin’s formulation, Burn! while an examination of the struggles of the colonized (Dolores) against the colonizer (Walker) is also an examination of the struggles of labor (Dolores) against capital (Walker). The struggle of the wage slave is joined with the struggle of the chattel slave.

And it is with this focus on economic concerns that Burn! leaves the shadow of Battle of Algiers and stands on its own with an unique ideological agenda. And that is manifested in the second half of the film when Walker serves as an agent of the Royal Sugar Company and not Her Majesty’s Government. Pontecorvo and his collaborators are responding to a global shift from a colonial to a post-colonial paradigm. For example, at the time of the film’s initial release, the world has witnessed the rise of Mobuto in Zaire following the Congo Crisis. Though ostensibly a figure of national liberation, Mobuto maintained cozy relationships with Belgium and France --the very colonial powers that had just been expelled -- as well as the United States. Corporate interests in Zaire’s natural resources would also greatly enhance Mobuto’s wallet; indeed, Mobuto would come under severe criticism from Naipaul in the form of the character Big Man in the novelist’s post-colonial masterpiece A Bend in the River. The military coup leaders who depose and execute Teddy Sanchez and then enter into their own cozy and profitable relationship with the Royal Sugar Company share some aspects with Mobuto including that of corruption.The presence of the Royal Sugar Company in the film demonstrates the new, subtler, and indirect methodologies of control exercised by the European powers over formerly controlled territories. The revolution has been hijacked, and the essential hegemonic structure is maintained. Insightful American audiences further cannot but help to find resonance in the Walker’s shifting job description. As mentioned above, his first employer is the Admiralty. His second employer is the Royal Sugar Company. In some respects, he is the embodiment of the military-industrial complex President Eisenhower warned of early in 1961.

In one of the most famous monologues from the film, Brando’s Walker addresses Sanchez and his colleagues as they plan their revolution: “Gentlemen, let me ask you a question. Now, my metaphor may seem a trifle impertinent, but I think it's very much to the point. Which do you prefer - or should I say, which do you find more convenient - a wife, or one of these mulatto girls? No, no, please don't misunderstand: I am talking strictly in terms of economics. What is the cost of the product? What is the product yield? The product, in this case, being love -uh, purely physical love, since sentiments obviously play no part in economics.” xi Walker goes on at length to specify the difference in prices between a wife and a prostitute. He then concludes, “Which, gentlemen, is more important - and more convenient: a slave or a paid worker?” xii The plantation of Queimada has been the location of the battle between colonizer and colonized. Michael T. Martin interprets this speech as representative of the shifting balance in economic forces from mercantile colonialism to open market capitalism “while invoking Enlightenment principles against a competing, although declining, hegemonic state (Portugal) on behalf of an ascending one (England).” xiii In Martin’s formulation, Burn! while an examination of the struggles of the colonized (Dolores) against the colonizer (Walker) is also an examination of the struggles of labor (Dolores) against capital (Walker). The struggle of the wage slave is joined with the struggle of the chattel slave.

And with the mention of the military-industrial complex, we now turn to the third and final layer of my onion: Burn! is a work of historical subversion. The choice to alter the colonial rulers of Queimada from the Spanish to the Portuguese may have been one made from business necessity, but it was also a liberating choice. The film is by no means the standard traditional historical costume epic that were flooding cinemas at the time: Man for All Seasons, Beckett, or Anne of a Thousand Days to name a few. Nor does it attempt to relay an “objective” rendering of a particular historical moment or figure. Rather, the history being deployed here is that of geschichte, or, as described by Raymond Williams, an on going dialectic between past and present. Both influence each other. And as much as Burn! is about the depredations of the European colonial powers, it is as much about the United States and its neo-colonial war in Vietnam. A few illustrations are needed. First, let us take the name of Brando’s character: William Walker. The historical William Walker was an American adventurer and filibuster who was intent on increasing the power of Southern slave-owning states by establishing English-speaking colonies in Central and South American states. He was briefly President of Nicaragua before a coalition of Central American armies executed him. The historical Walker and his doppelganger the fictional Walker stand as symbols of American military adventurism for the pursuit of profit. Such a figure has a clear connotation for a nation engaged in a long-term conflict in Southeast Asia.When Walker returns to Queimada, he provides a number of lessons to the Queimadan rulers and British officers on the nature of the revolutionaries they are hunting. (Indeed, Walker often serves as Pontecorvo’s mouthpiece for the concepts of historical materialism). The rebels only have a life to lose, Walker informs these elites, while the soldiers hunting them have family, property, and livelihood at risk. Sir William concludes that this makes the rebel that much more intractable. Celli states, “These considerations echo the strategy of guerilla leaders like China’s Mao Tse-tung or the Vietnamese Ho Chi Minh. Brando would have a chance to repeat similarlines in his performance as Kurtz in Apocalypse Now (1979), Francis Ford Coppola’s adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s nineteenth-century English adventure novel, Heart of Darkness.”

In fact,Pontecorvo would deploy a number of different images that would be familiar to American audiences witnessing the Vietnam War through television news programs. I will name just two. First, the Quiemadan Government forcibly removes the island’s population from its villages to “secure” controlled locations in order to deprive the revolutionaries of a support structure; the parallels with the Defense Secretary McNamara’s Strategic Hamlet Program are clear. Second, the British Army – as the Portuguese did before them – burn down the island’s vegetation to deprive the revolutionaries of places to hide. As Pontecorvo presents these scenes, though, they resemble images of the US Air Force dropping napalm on the Vietnamese jungle. The use of fire as a weapon has a similar intent as well. By utilizing geschichte as the means by which history is communicated, Burn! is a much more dangerous film for American audiences than Battle of Algiers. Whereas for the latter, the audience could comfort itself in the mythologies of the United States as world liberator (and asliberated colony) – that what was depicted on screen was a product of a purely European-style of domination – they have a much more difficult time finding safety in those mythologies. For with geschichte, Pontecorvo is able to link explicitly European and American strains of expansionist methodologies and is thus indicting American intervention in South Vietnam as part and parcel of the colonial enterprise. I quote Pauline Kael early on United Artists’ nervousness at releasing this film. Perhaps they were right to be nervous.The reputation of The Battle of Algiers continues to soar.

Burn! has not disappeared down a memory-hole the way that Kaufmann might have hoped, but its image still needs to be rehabilitated. A process, by which I might add, has begun. Martin, whom I mentioned earlier, has contributed intriguing and original research on the film. Nonetheless, I fear that Gary Crowdus in advocating for Sidney Poiter to have played the role of Dolores rather than the unknown Evaristo Marquez does not fully comprehend Pontecorvo’s artistic decision-making process in hiring non-actors to play the roles of his revolutionaries; Marquez was an illiterate Colombian sugarcane worker, and Pontecorvo believed that he could bring an authenticity to the role of Dolores that would elude a professional actor. What would help immeasurably would be the release of the 132-minute version of the film in the United States. The 112 minute truncated version is the only one currently available in this country, and, unfortunately, it is the one with which I had to work.

Burn! was and remains an important film and should be as much of our conversation as Battle of Algiers. As the United States is currently mired in two wars in Asia (that have, for many of the peoples involved, imperial overtones) and may be joining a third in North Africa, Burn! has much to offer audiences today as it did during the Vietnam Era. Indeed, perhaps the military and civilian Pentagon officials I mentioned earlier should screen this work as well. It might provide them some additional context that Battle of Algiers does not provide.

i Stanley Kaufmann. “This Man Must Die/Burn”, The New Republic. 11/14/60, Vol. 163 Issue 20, p20-32.

ii Kafumann, Ibid.

iii Pauline Kael. 5001 Nights at the Movies. (New York: Holt, Rineheart, and Winston, 1985), pp. 109-110.

iv Kael, Ibid.

v Stefan Kanfer. Somebody: The Reckless Life and Remarkable Career of Marlon Brando. (New York: Vintage, 2008),p. 264.

vi Kael, Ibid.

vii Carlo Celli, Gillo Pontecorvo: From Resistance to Terrorism. (Lanham, MD: The Scarecrow Press, 2005), p. 78.

viii Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism. (New York: Vintage, 1993), p. 272.

ix Celli, Ibid., pp. 79-80.

x Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth. (New York: Grove, 1968), p. 93.

xi Burn! dir: GIllo Pontecorvo. United Artists. 1969.

xii Ibid.

xiii Michael T. Martin. “Podium for Truth? Reading Slavery and the Neocolonial Project in Film”. Third Text.November 2009. Vol. 23, Issue 6. Pp. 717-731.

xiv Celli, Ibid., p. 83.

xv Gary Crowdus. “Burn!”, Cineaste. 00097004, Jul93, Vol. 20, Issue 1.