After two new episodes, it is safe to report that the new season of Castle is as entertaining as the first season's ten episodes. While the main focus is the romantic comedy featuring the two leads, the police procedural is more convincing than most TV shows and there's some terrific family comedy regarding our hero's household. This remains one of the most satisfying hours of television currently on the air.

After two new episodes, it is safe to report that the new season of Castle is as entertaining as the first season's ten episodes. While the main focus is the romantic comedy featuring the two leads, the police procedural is more convincing than most TV shows and there's some terrific family comedy regarding our hero's household. This remains one of the most satisfying hours of television currently on the air.

Wednesday, September 30, 2009

Castle season two

After two new episodes, it is safe to report that the new season of Castle is as entertaining as the first season's ten episodes. While the main focus is the romantic comedy featuring the two leads, the police procedural is more convincing than most TV shows and there's some terrific family comedy regarding our hero's household. This remains one of the most satisfying hours of television currently on the air.

After two new episodes, it is safe to report that the new season of Castle is as entertaining as the first season's ten episodes. While the main focus is the romantic comedy featuring the two leads, the police procedural is more convincing than most TV shows and there's some terrific family comedy regarding our hero's household. This remains one of the most satisfying hours of television currently on the air.

Tuesday, September 29, 2009

Starting FINGER ON THE TRIGGER without a star

From: SO YOU WANT TO MAKE MOVIES

From: SO YOU WANT TO MAKE MOVIESMy Life As An Independent Film Producer

by Sidney Pink

Spain was becoming a mecca for almost every unemployed American actor in Europe, and we were able to recruit a cast of all English-speaking professionals. James Philbrook, one of the stars of the TV series Wild West, made his home in Madrid, and while his name value was not too important, Jim was a fine actor and played in almost every film I made for five years. He was a good-looking, rugged, typically American six-footer, and he saved my neck on many occasions. We also sent some of our better Spanish actors to an English clinic we ran for those who wanted to learn to read their lines in English. The signing of Victor Mature gave us a badly needed shot in the arm, but unfortunately, it was only temporary.

We deposited the money with Tony Recoder and we received our first demand from Mature. He would not get within ten feet of a horse and he demanded to be allowed to bring his own stand-in stunt man, paid for by us. Tony learned Victor Mature had a mortal fear of horses and had never ridden in his entire movie career. I found this hard to believe, but all his riding and chase sequences were shot on a dummy horse or with his stand-in, who bore an amazing likeness to him from a distance. We had no choice but to agree.

Victor's next demand was for two first-class cabins aboard the Queen Mary since he refused to fly. Besides his fear of horses, he was also afraid to flying. The cost of these cabins was triple the two first-class airfares promised in his contract. Then he demanded five nights lodging at the Savoy Hotel in London for his recuperation from the long ocean voyage. He demanded the royal suite and his daily expense allotment to begin as of his departure date from Los Angeles, and for his stay in London, the allotment would be doubled. He also insisted on a royal compartment on the train from London to Madrid.

We complied with all of Mature's demands. Our starting date was set for two weeks after he left Los Angeles for New York and embarked on the Queen Mary. We prepared everything around that date, and expected him to arrive in Madrid two days prior to our start.

When we heard nothing from either Mature of his stunt man by Sunday, I called Tony to check on his whereabouts. We had scheduled an easy first day, but we did need Mature for the opening shots. Tony was as upset as I was and promptly began to check on the whereabouts of our missing star. He called back to inform me that Mature had arrived in London, enjoyed our hospitality at the Savoy, and left with his stunt man for the train station, but he never made the train. He disappeared into the city as mysteriously as a London fog. How anyone as well known and as big as Mature could disappear was an enigma, but disappear he did, and I had to start without him.

Our first-day schedule called for scenes of the exterior of the Yankee fort now held by the Confederate troops. Our opening shot was Victor Mature riding up to the fort, where he requests food and water for his men. They are hungry and desperately thirsty after their arduous trek across the deserts of New Mexico. The fort is the only oasis for miles, and the men are without water. The Confederate troops (dressed in Yankee uniforms) prevent them from entering the fort. Their captain (Jim Philbrook) refuses the request for water, and a fight takes place between the two groups.

Had Mauture been there it would have been an easy day of work in preparation for our grueling schedule, but he didn't show up. How the hell do you shoot a movie without your leading man who appears in just about three-fourths of the picture? I didn't know the answer, but I had to get by. We shoot three of the five weeks allotted for the film without our star, and to this day I don't know how we achieved that almost impossible accomplishment.

Monday, September 28, 2009

Eastwick

Getting a star for FINGER ON THE TRIGGER

From: SO YOU WANT TO MAKE MOVIES

From: SO YOU WANT TO MAKE MOVIESMy Life As An Independent Film Producer

by Sidney Pink

Spain contributed the cameraman (Antonio Macasoli), the cutter, three Spanish leads, the lab and sound studio, and all of the exteriors. The American contribution consisted of the lead, the director, and most of the supporting cast. We used almost every American actor in Spain in FINGER ON THE TRIGGER, and it looked, smelled, and tasted like the real thing. Since I was almost completely broke and if I didn't work I wouldn't eat, I named myself as the director. There was no other director around who had ever done a Western, so there was no argument. I paid myself $10,000 for the job and was able to survive. We still needed a star.

Tony Recoder submitted a list of the William Morris stars available for the picture; it included the name of our unanimous choice, Victor Mature. Mature (a former larger-than-life star) appeared in some of Hollywood biggest epics and was still a box-office draw in Europe. He hadn't worked for a long time, but I didn't know why and neither did Tony. We started negotiations, and he agreed to work six weeks for $25,000 to be paid in full in advance of his arrival. We compromised by putting the money in an escrow account controlled by the Morris office, and Mature signed the contract. Signing him for the first Western ever made in Europe was a great coup for Spain and for the future of Westerns in Europe. Mature had made many Westerns, all with important co-stars and his name was associated with big-budget outdoor films. Then we learned why he was available. He issued a series of demands immediately after the money was deposited.

But first, in order to eliminate all traces of our previous failures, Sacristan and Recoder insisted that FINGER ON THE TRIGGER be made under a new banner, and thus FISA was born. The initials stood for Films Internacionales Sociedad Anonyma, and the company was duly formed and registered as a film producer under Spanish law. The owners were Mole Richardson, Antonio Recoder, and Pepe Lopes Moreno as my representative. We subleased my headquarters at San Telmo to the new company, and all my equipment was turned over as the cost of the stock received by Lopez Moreno. We then started scouting for appropriate locations.~Luis de los Arcos led us to the southernmost part of Spain to a city named Almeria, located east of the Costa del Sol and Malaga but west of the Costa Brava and Barcelona. The city, actually a small Moorish village, sat on the Mediterranean coast in the most arid part of Spain, totally ignored by the Spanish. The roads to Almeria were tortuous and pothole-ridden, and some were totally unpaved. The area surrounding the town was Arizona, New Mexico, and Nevada rolled into one - a barren wasteland unmarked by anything more than a scrub and sagebrush for mile after mile. To quote Rory Calhoun, it was "acres and acres of nothing but acres."

But first, in order to eliminate all traces of our previous failures, Sacristan and Recoder insisted that FINGER ON THE TRIGGER be made under a new banner, and thus FISA was born. The initials stood for Films Internacionales Sociedad Anonyma, and the company was duly formed and registered as a film producer under Spanish law. The owners were Mole Richardson, Antonio Recoder, and Pepe Lopes Moreno as my representative. We subleased my headquarters at San Telmo to the new company, and all my equipment was turned over as the cost of the stock received by Lopez Moreno. We then started scouting for appropriate locations.~Luis de los Arcos led us to the southernmost part of Spain to a city named Almeria, located east of the Costa del Sol and Malaga but west of the Costa Brava and Barcelona. The city, actually a small Moorish village, sat on the Mediterranean coast in the most arid part of Spain, totally ignored by the Spanish. The roads to Almeria were tortuous and pothole-ridden, and some were totally unpaved. The area surrounding the town was Arizona, New Mexico, and Nevada rolled into one - a barren wasteland unmarked by anything more than a scrub and sagebrush for mile after mile. To quote Rory Calhoun, it was "acres and acres of nothing but acres."

Even in the so-called winter the place was hot. The sun blazed down from a normally cloudless sky like a huge blast furnace, and one any summer day you could actually fry eggs on those rocks. It was more like the American West and the American West, and it was to become the location for more Western movies than any place outside the U.S. itself. It had sand dunes and valleys, peaks and canyons, but above all it had no telephone poles or any other visible accouterments of twentieth-century civilization. In short, it was perfect for shooting outdoor Westerns.

LAWRENCE OF ARABIA was the first movie to be shot in that remote part of Spain. The dunes and the desert battles were shot in the sands of Almeria. There were plenty of horses around, since the area was populated mostly by gypsies who owned at least one horse per family. Perhaps not our Western cayuses, but a horse is a horse is a horse. Anther plus was that those gypsies made sensational Indian extras. Thus a new Hollywood Western location was discovered, and we were ready to shoot.

(Pink's calling FINGER ON THE TRIGGER "the first Western ever made in Europe" is contradicted by his earlier report that the Germans had revived the Western with the Winnetou films. FINGER wasn't even the first English language Western made in Spain - the Michael Carreras directed SAVAGE GUNS was made in 1962 and starred Hollywood actors Richard Basehart, Alex Nicol and Don Taylor.)

Sunday, September 27, 2009

Cougartown

Saturday, September 26, 2009

Preparing FINGER ON THE TRIGGER

From: SO YOU WANT TO MAKE MOVIES

From: SO YOU WANT TO MAKE MOVIESMy Life As An Independent Film Producer

by Sidney Pink

Arthur Brauner and the German production companies had revived the Western through a series of Indian pictures starring Lex Barker. They depicted the German vision of American Indians and bore as much resemblance to our actual history as the German countryside emulated our Old West, but they were huge successes all over Europe and the Far East. They were coining money, and Vittorio was shrewd enough to latch onto the idea and improve upon it. He had no script or story idea, except it had to include Indians and be full of action scenes. I was to provide the script, to be approved by the Italian company, and I had to face the reality that if I failed on this film, I was finished as a producer. My very last cent was going into this final gamble, and I must admit to many qualms about my ability to pull it off. But Cagney was still with me, so "damn the torpedos, full speed ahead."

Although it was Luis de los Arcos who destroyed Esamer, I didn't think it was his fault. He worked as hard as anyone, and the mistake was mine. I should have realized he was unfit to be a director and too inexperienced to handle such a difficult picture. No one could deny Luis' brilliance as a writer, so we collaborated on a script based on his original story of an event that took place right after the Civil War. He called it EL DEDO EN EL GATILLO, literally translated as FINGER ON THE TRIGGER, a whale of a title for a Western. We kicked the story line around together, and in twelve days we had a finished screenplay in English and Spanish...

It was an excellent script for a Western, accepted by the Italians with great enthusiasm but now it needed a star.

First we cast all coproduction requirements. Vittorio chose for his leading lady a beautiful French actress, whose dual nationality allowed her to be classed as an Italian actress. Her name was Silvia Solar and she spoke no English, but her considerable name value in France made her very important to Annibaldi. Silvia promised to learn her part in English so we could dub it more easily. She was not only beautiful, but also intelligent enough to realize this film could get her international attention in this new era of worldwide production. Silvia kept her word and hired an English tutor to help her with her pronunciation. Her part was so well dubbed it actually appeared as though she had done it herself. We agreed to let the picture carry the name of an Italian director for the European market, and so Annibaldi hired a ghost director who was paid for the use of his name. This, together with the script that in Italy and Europe bore the name of an Italian author, fulfilled all the Italian coproduction requirements.

Friday, September 25, 2009

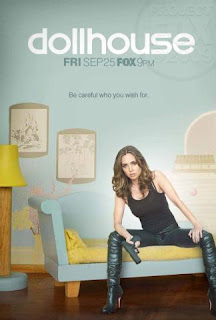

Dollhouse season two begins tonight

Thursday, September 24, 2009

Sidney Needs To Make A Western In Spain

From: SO YOU WANT TO MAKE MOVIES

From: SO YOU WANT TO MAKE MOVIESMy Life As An Independent Film Producer

by Sidney Pink

(After the success of THE CASTILIAN, Pink produced PHANTOM OF THE FERRIS WHEEL, aka PYRO, aka WHEEL OF FIRE, directed by Julio Coll, which did well. Next came ROMEO AND DELILAH, aka DELILAH, aka OPERACION DALILA, directed by screenwriter Luis de los Arcos, which turned out so badly that Pink could not find a distributor for it. In desperation, Pink needed to make money and an opportunity to make commercials for Pepsi in Spain for the Spanish speaking market rescued him.)

I still didn't have enough money to develop any further projects and was almost at the end of my rope when I got lucky again. On one of my visits to Rome I met Vittorio Annibaldi, who suggested a coproduction between his Italian company and our Esamer. It was a great idea, but since neither of us had any money, it never got off the ground. Now he called me with the news he had concluded a deal with an important Italian distribution company to make a Western, but he had no knowledge of how or where to start. He assumed that as an American producer, I would know how to make a Western feature, and he needed my expertise.

Although I had learned a great deal on the Tex Ritter sound stages, I really didn't know too much about the production aspect, but I was able to bluff my way through his avid questioning. I had one little problem: I needed $50,000 (3 million pesetas), a very substantial sum in Spain, and I had no idea where to find the money.

Then I met Jose Lopez Moreno, a young roly-poly Spaniard with a strong desire to become a film producer. Jose, or Pepe as he was called, worked around the fringes of showbiz in Spain, but he had never been involved in anything really significant. Although he had no money, he purportedly was able to find folks who would invest in projects that promised tremendous returns. Pepe introduced me to Gregorio Sacristan, the head of the Spanish division of the Mole Richardson Equipment Leasing Company. Mole Richardson, a London-based company, was one of the largest suppliers of motion-picture equipment, with branches all over the world including Hollywood, California.

I met with Gregorio, who was very interested in getting involved with Spanish-American coproduction. Sacristan was a thin, nervous Spaniard of obvious Moorish ancestry. He was swarthy, with coal-black eyes which (almost like Las Vegas dice) darted about nervously. He always wore a worried expression, which I later learned came from a severe gastric ulcer. He was a complete workaholic, and his office hours were all day every day, including Sundays. Gregorio tried to play it tough, but he was really a pussy cat. I am sure part of the problem causing his chronic ulcer was his desire to be a ruthless tycoon that clashed constantly with his innate inability to take advantage of anyone. Gregorio was too heavily endowed with the milk of human kindness, which others around him constantly curdled.

Tony Recoder was the attorney of record for Mole Richardson (it seemed he represented every American of British company in Spain), so he did nothing to discourage the potential wedding of Esamer and Mole Richardson of Spain. I think Tony Recoder was possibly the greediest man I have ever known. His insatiable ambition was not soley for money and prestige; to him it was of extreme importance to be involved in every deal made in the Spanish movie world, a goal he came awfully close to reaching. Tony was about five feet ten, with a small mustache that was annoying in its precision and neatness. (It seemed to have exactly the same number of hairs on each side of his nose.) His reputation was no worse than the average Spanish lawyer, but in contrast to how I felt about Luis Sanchis, I never really trusted Tony. His hair was black and he was a good-looking Latin type. I am sure the ladies loved him, but I never liked Tony.

Gregorio and I, together with Tony and Pepe, negotiated for weeks with little or no success until another stroke of luck hit us. The legendary Buster Keaton was in Spain shooting A FUNNY THING HAPPENED ON THE WAY TO THE FORUM, the case of which included almost every great comic of the era. Pepsi-Cola America was introducing its new drink, Bubble-Up, to compete in the non-cola market dominated by Seven-Up. The goal was to launch the product with a huge comedy campaign, and someone in the creative department came up with the idea of using Buster Keaton as the personality to introduce it.

(Pink made the commercial, loved working with Buster, and had some money for the movie project.)

Now that I was able to approach Mole Richardson with a cash participation of our own, we made a deal. Mole Richardson would invest their materials and cash up to 5 million pesetas, while we were to put up the equivalent of $25,000 in either actors or cash. The film had to be a Western. We were to sign an internationally recognizable name as our lead and provide the director. Annibaldi got distribution rights to Europe and we retained rights to the rest of the world. Total budget for the film was $200,000 (14 million pesetas), large for a Spanish film.

Wednesday, September 23, 2009

Sidney discovers Soledad

From: SO YOU WANT TO MAKE MOVIES

From: SO YOU WANT TO MAKE MOVIESMy Life As An Independent Film Producer

by Sidney Pink

(After the success of THE CASTILIAN, Sidney Pink created a new movie company in Spain and then set out to make a movie called PHANTOM OF THE FERRIS WHEEL, aka PYRO. The leading role went to American stars Barry Sullivan and Martha Hyer.)

In Spain I finished my casting with a flair. We had only a few more parts to fill, so I made certain every one of my actors could play their parts in English. I discovered a young Spanish actor, Fernando Hilbeck, who spoke perfect English with just the right touch of accent needed to make his part credible... Fernando was damned good and he appeared in almost every film I made in Spain.

In making THE CASTILIAN, we discovered a sixteen-year-old blonde beauty, Soledad Miranda. I was so impressed by her native ability that we put her under long-term contract with our company. She played the part of the young daughter of the owner of the carnival who falls in love with the totally unresponsive ferris wheel repairman. It was a nothing role, but she did well with it. The rest of the casting was for small parts, so I allowed Julio Coll to select the rest of the actors with the proviso that they must be able to do their dialogue in English.

Tuesday, September 22, 2009

Finishing THE CASTILIAN

From: SO YOU WANT TO MAKE MOVIES

From: SO YOU WANT TO MAKE MOVIESMy Life As An Independent Film Producer

by Sidney Pink

We were almost out of money when we finished principal photography. The picture was completed, but lacked the battle scenes to flesh out the concept of the fierce hatred between the two nations. EL CID was playing to packed houses and its battle sequences were outstanding. To be successful, we would have to exceed the spectacle and gore of those battle scenes. Al Wyatt, who had just completed the action scenes of ROMAN EMPIRE, was available and willing to devote his expertise to making our action even more exciting and sweeping in its flow. He needed $50,000 for a budget that would include his own fee, and he guaranteed a huge production, equal to anything that he yet been made.

All I needed was the $50,000. I had exhausted almost every resource when a thought struck me. Warner Bros. had indicated they were pleased with the footage I sent them to keep them up to date on our progress. I called Ben Kalmenson again and told him of the problem. I guaranteed that every cent of the money would go into the production and nowhere else. He responded by sending Dick Lederer to Madrid to look at our work print.

Dick looked at the rough cut, talked with Rich Meyers and Al Wyatt, and made some very constructive criticisms that helped us greatly. I know that some credit for the ultimate success of the picture belongs to Dick. He returned to California, and shortly thereafter we received our check and completed the picture. Now VALLEY OF THE SWORDS was in the can. The only thing remaining was to convert that into money.

The trials and tribulations of that production were so numerous and painful that I really hate to look back at those days. If there had been no Espartaco Santoni, it might have been different, but I don't think so. To any would-be producers who look to Europe as a haven, I say forget it. I made fifty-one films there, and I never found an easy way to do it. ANGRY RED PLANET, TWONKY, and even BWANA DEVIL never presented the production headaches we faced in even our smallest European production. I survived because I needed to survive, but there was no fun in it.

And so it was finished. VALLEY OF THE SWORDS was negative cut, and sound effects were put in. This also proved a gigantic task, and we could find no Spanish editor who was capable of accomplishing it. We hired Kurt Herrnfield (also from the Bronston company) who did the job quickly and thoroughly. The difference that proper sound effects make to a picture are incredible. The whole film came to life after Kurt was finished, and only then did I feel we had made a good picture.

We also hired a yound Spanish composer (a friend of Luis de los Arcos) who wrote a fine musical score that won several awards in Spain and Latin America. As promised, we gave the title song to Bob Marcucci and we recorded it with Frankie Avalon. Bob also wrote a beautiful love song that I had high hopes for, but for which no market appeared. I still think it's a beautiful melody.

We had been unable to get any lab financing in the States due to the Spanish law dictating that all production lab work had to be done in Spain. But we finally found a new lab in Los Angeles, called Panacolor, that was developing a process that made possible the printing of color images on black and white stock. This lab desperately needed a film to demonstrate the quality of the Panacolor process. The president of Panacolor was Harry Eller, and he wooed and pursued us after we announced our Warner release.

Harry and I worked out a deal giving us up to $100,000 in lab credits as well as $25,000 in cash to be used in technical work such as titles and other effects that his lab was unable to do. In exchange, we gave them exclusive printing in the U.S. and Canada for all our future productions. It was a good deal for both parties. Panacolor had an important major release to launch its new process, and I had the comfort of knowing that once we delivered our negative, we had no further lab problems. Harry and I got along so well together that he subsequently resigned from Panacolor and joined me as president of our new company, SWP Productions.

The Panacolor lab began to make the prints of our film. The system was not functioning too well - they had to run about ten prints for every acceptable one, and Warner's opening order was for 150 prints. About sixty prints were finished when Panacolor gave up and turned the job over to Technicolor. The Panacolor prints we accepted were of magnificent quality, particularly the blues, but if forced to make the 350 prints that were ultimately made by Warner, Panacolor would have gone bankrupt. Panacolor never did get rid of the production bugs in the system and ultimately went out of business.

Dick Lederer did not like the title VALLEY OF SWORDS, and with our permission it was changed to THE CASTILIAN, which I accepted although I didn't like it. I bowed to Dick's superior experience, but now as a Monday morning quarterback, I can see that I was right. The picture never did as well in the U.S. as it did where it played under another title. Despite lackluster business, THE CASTILIAN opened to great reviews in New York and L.A. The dean of all movie critics, Bosley Crowther, spoke highly of its realism and magnificent costumes and sets. He also praised the action scenes and commented that THE CASTILIAN was the picture EL CID should have been.

Despite the fact that we won some of the major awards in South America, including the prestigious Golden Condor (accepted for us by Cesar Romero at a banquet in Los Angeles), we found Warner Bros. to be no different that AIP or Columbia. Again we were subjected to "creative bookkeeping". THE CASTILIAN became Warner's second-largest grossing film in Latin America at that time (only GIANT did better). Yet according to Warner's records, our profits were only some $4,000. Warner's accounting in the U.S. and elsewhere was even more creative. Again I had problems with my associates, and Joe Leonard raised holy hell with me. We were forced to sue and ultimately settled for an acceptable profit, but I never did learn how much the picture really earned. It was a huge success under British Lion in the Commonwealth, and of course in Spain it became the number one box-office attraction.

Despite the immediate success of the picture, there was no market for Espartaco. It became the only film he ever acted in, and he returned to the anonymity he so richly deserved. I was now back in Spain with one notch on my gun and looking for new fields. I found them.

(Of course the Bronston movie was THE FALL OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE and Espartaco Santoni continued to be a celebrity in Spain, though his movie career wasn't spectacular. Pink obviously never saw director Mario Bava's LISA AND THE DEVIL or he would have known that Santoni did indeed go on to act in other movies.)

Monday, September 21, 2009

IL MOMENTO DI UCCIDERE

IL MOMENTO DI UCCIDERE

IL MOMENTO DI UCCIDERETHE MOMENT TO KILL

French: LE MOMENT DE TUER

German: DJANGO-EIN SARG VOLL BLUT

DJANGO A COFFIN FULL OF BLOOD

Director - Anthony Ascott (real name: Giuliano Carnimeo) 1968

Cast: George Hilton (Lord), Walter Barnes (Bull), Loni von Friedel (Regina), Renato Romano, Arturo Dominici (Forrester), Rudolf Schundler (Judge Warren), Remo De Angelis (Dago), Giogrio Sammartino (Trent), Carlo Alighiero (Forester), Ugo Adinolfi, and Horst Frank (Jason Forrester).

An Italo-German Coproduction

P.C.E. Produzioni Cinematografiche Europee, Euro International Films (Rome), Terra Filmkust (Berlin)Produced by Vico Pavoni

Story by Tito Carpi, Enzo G. Castellari

Screenplay by Tito Carpi, Francesco Scardamaglia, Bruno Leder

Set Designer Alberto Boccianti

Costumes Enzo Bulgarelli

Assisted by Stefano Bulgarelli, Francesca Romana Cofano (c.s.c.)

Assistants to the Director Fabio Piccioni, Hans Billian

Continuity Vittoria Viscrelli

Production Inspector Cecilla Bigazzi

Cameraman Mario Pastorino

Assist. Cameraman Michele Pensato

Sound Engineer Massimo Jaboni

Make-up Sergio Angeloni

Hair Stylist Lina Cassini

Editor Ornella Micheli

Music by Francesco De Masi

Directed by the composer

musical copyright National Music-Milan

The song "Walk By My Side" by De Masi Alessandroni-De Mutisis sung by Raoul

English version Criterium Production

Syncronization C.D.S.

Filmed at the Cinecitta Studios

Director of Photography Stelvio Massi

Technicolor - Techniscope

Production Manager Dino Di Salvo

Distributed by Euro International

Missing gold was not an unusual catalyst for a Western plot, so perhaps these filmmakers felt that doing the old story in Western costuming, but with the look and atmosphere of an "Old Dark House" thriller would make it unique. Perhaps it was, but they should have made certain that an audience had something to care about before spending so much time on guys creeping around in the dark.

Creating the characters of Lord and Bull, a duo of former confederates who became hired gunmen, and then casting the roles with George Hilton and Walter Barnes, was a step in the right direction. But these were the kind of characters suitable for an expansive adventure story, not guys about whom suspense could be generated in an "hide and seek" gun battle.

Director Giuliano Carnimeo and Cinematographer Stelvio Massi came up with a stylish look for the film, with unusual camera angles and inventive staging. But, in collaboration with Editor Ornella Micheli and Composer Francesco De Masi, they weren't able to give this enough of a pace to keep things from getting pretty dull. There was plenty of time for sharp audience members to guess all of the upcoming plot twists. What perhaps wasn't predictable was the odd freeze frame ending.

There were many familiar faces to enjoy seeing again, but no one delivered a really notable performance. The casting of Arturo Dominici as Horst Frank's father was an interesting decision, but unfortunately it didn't pay off with an interesting result.

Walter Barnes expressed regret over his performance as Bull. He felt he could have done so much more with the role, if he hadn't been so distracted by the divorce proceedings brought against him by his wife in Germany.

(Thank you to Eric Mache for a chance to see the English language pre-record from Holland.)

Sunday, September 20, 2009

Broderick Crawford in THE CASTILIAN

From: SO YOU WANT TO MAKE MOVIES

From: SO YOU WANT TO MAKE MOVIESMy Life As An Independent Film Producer

by Sidney Pink

We ended principal photography with only ten days left to finish with Cesar. We needed to complete his battle close-ups as well as his voice dubbing in that time, due to his absolute commitment to report to the DONOVAN'S REEF location for immediate shooting. Thanks to the wizardry of Rich Meyers, and to the luck that brought Al Wyatt to Madrid to direct the action scenes of ROMAN EMPIRE for Bronston, we met the deadline. Gentleman that he always was, Cesar promised to return or do anything that might be necessary for completion. He volunteered to do it with no further payment and he meant it - a truly remarkable man.

During the early days of production, we were confronted with our last casting problem. The cameo role of King Sancho of Navarre, the hard-drinking monarch of that kingdom, was the last role open for an international name. It called for an actor of real stature, and the scene in which he destroys the wine cellar of the Castilian lord who was protecting Fernan Gonzales could yield an Oscar for supporting actor. I had not cast the part because I saw it as a perfect vehicle for Broderick Crawford whom I met on GOLD LOVERS.

I don't suppose there are too many people now who remember how important Brod Crawford's name was in 1963, but he was one of the few "name" actors who had accepted and joined TV, and his series was being played all over the world. He was popular in every major country, including Japan. Getting Crawford not only meant acquiring prestige and a fine actor, it also meant additional box-office dollars. I waited until the last possible moment to cast the role in the hope that I could get Brod for the part.

I discussed the part with Paul Ross, who continued as our press agent and represented Brod as well. Paul told me Brod Crawford was remarrying and wanted to come to Europe for his honeymoon. If I could coordinate our shooting schedule with his free time, he would come to Spain with his bride. When I inquired what he would cost, I was told he wanted two round-trip first class fares, all expenses in Madrid paid for, and $5,000 for incidentals to be paid to him in cash on his arrival. Despite Espartaco's attempts to stop me, we changed our schedule to get Brod Crawford's entire role shot in one week.

We got even luckier: Brod called to tell me he had been able to clear three weeks of hiatus time and would arrive early. He arrived at the Barajas airport with his young wife of forty-eight hours; she was breathlessly excited and he was hopelessly drunk. There was no nicer person than Brod Crawford, and he was in the same professional class as Cesar Romero, but he was an alcoholic. His normal breakfast consisted of a mug full of the most powerful of Spanish brandies (150 proof) covered with about two teaspoonfuls of coffee. For the rest of the day he nursed either Scotch of brandy in a bottle he always carried with him.

We tucked him into bed at the Hilton upon his arrival and kept him sober for two days while he went over the script with us. He gave us his word he would be sober for the big scene where he played the drunken king. He promised not to touch a drop for twenty-four hours before the scene, in exchange for our commitment to allow him full freedom to do as he pleased at other times. Brod was a real pro, and he never missed a call or scene. The problem with his drinking was his inability to speak lines. He not only forgot them, he was unable to speak intelligibly even though he could go through all the action the scene required. Everyone loved that big, shaggy, warm-hearted kid.

The whole Brod Crawford incident ended badly. He came into his big scene cold sober and proceeded to fluff every action. After three hours of failure, we gave up and let him drink again. He got through the scene, but we never knew what he said for dialogue. The only thing that saved the voice dubbing was his very distinctive gruff voice. Everyone knew it was Brod Crawford talking so the bad lip sync got by. I liked Brod, but I swore never to work with a drunk again - until I met Victor Mature.

Saturday, September 19, 2009

IL SEGNO DI ZORRO

IL SEGNO DI ZORRO

IL SEGNO DI ZORROFrench: LE SIGNE DE ZORRO

German: ZORRO, DER MANN MIT DEN ZWEI GESICHTERN

Spanish: EL CAPITAN INTREPIDO

U.S.: DUEL AT THE RIO GRANDE and THE MARK OF ZORRO

Director - Mario Caiano 1962

Cast: Sean Flynn (Don Ramon Martinez), Daniele de Metz (Manuela), Gaby Andreux (Senora Gutierrez), Walter Barnes (Mario), Mario Petri (Captain Martin), Armando Calvo (Gen. Gutierrez), Virgilio Dalgado Teixeira, Mino D'Oro (Don Luis), Gisella Monaldi, Guido Celano, Alfredo Rizzo, Piero Lulli (blacksmith), and Folco Lulli (Jose).Armand Galou, Vittorio Bonos, Gigi Bonos (wagon driver), Fernando Poggi, Aldo Cecconi, Pietro Ceccarelli, Manrico Melchiorre, Mimo Billi, Ugo Sasso, Tonio Selwart.

Screenplay by Casey Robinson, Guido Malatesta

Director of Photography Adalberto Albertini

2nd Unit Director of Photography Luigi Filippo Carta

Eastmancolor - Totalscope (Dyaliscope in Germany)

Music by Gregorio Garcia Segura

Music Publisher Campi

Film Editor Alberto Gallitti

Art Director Alberto Biccianti

Costumes Virgilio Ciarlo

Set Designer Bruno Cesari

Production Manager Luigi Nannerini

Assistant Director Alfonso Brescia

Sound Enzo Silvestri, Mario Morigi

Studios: Titanus - Farnesina

Exteriors Rome, Bari, Biarritz, Saint Jean De Luz

Produced by Fides (Paris). Compagnia Cinematographique Mondiale (Rome), Benito Perojo (Madrid)

Distri. Titanus

Prod. Reg. 2822

A pretty good tale of a son revenging the hanging of his father on a false charge of treason, was spoiled by someone's insistence that a Zorro connection needed to be made. Our hero was not Zorro, nor do we ever see him leave the "Z" found three times during the film. At one point he improvised a black mask to hide his identity, but he never donned a black cape, nor did he adopt the duo life of dandy-by-day, and masked avenger by night. If one could ignore the slapped-on aspect of this film, it could be enjoyed for some good action and high spirits. Ramon, a proud young Basque, was told by his mother that his real father was a Spaniard and that he now lived in Mexico. Don Martinez had written and asked Ramon to visit him.

With his faithful servant Jose, Ramon traveled to Mexico and quickly got into a cantina brawl with three thugs; Mario, Francesco and Romero. Having bested each of the three, Ramon found himself having to face all three at once with swords. Giving out a cry of "Ai-yei-yei-yei", Ramon and Jose raced off on their horses. Recognizing the cry, the three thugs realized that they have just picked a fight with a fellow Basque.

Having a Basque hero gave this swashbuckler a novelty at odds with the effort to turn it into a Zorro movie. Once again, though, if one could ignore the "Z"s, it worked. (Perhaps I could just dub down a copy of the video and edit out those annoying shots.)

Walter Barnes played Mario, one of the three Basque brawlers who sought out his countryman, and ended up joining the effort to topple the villainous General Gutierrez. While this role wasn't much different from the other brutish parts he'd played before, Barnes was able to infuse this effort with more humor and vitality than usual. His interaction with his two friends especially suggested more acting ability than most of his earlier performances had.

After his rather poor debut in IL FIGLIO DEL CAPITANO BLOOD (U.S.: THE SON OF CAPTAIN BLOOD), it was a pleasant surprise to see Sean Flynn looking lively in this lighthearted effort. From galloping about on horseback, or easily swinging up into a tree, or flying gracefully into a swordfight, Flynn easily bettered his previous performance. Did Mario Caiano, who had a minor job on CAPITANO BLOOD, see how to better use the American than director Tulio Demicheli did, or was it just personal growth by the actor?

Writer Casey Robinson was another holdover from CAPITANO BLOOD, but didn't show similar improvement. The plotting for IL SEGNO DI ZORRO was pretty standard. In order to get his hands on the silver mine, the villain killed our hero's father. And then, to swindle the government, he had his own men, disguised as bandits, steal the silver shipment. Naturally, our hero, in collaboration with an underground rebel group, foiled the plot and then joined the uprising of the populace which stormed the villain's villa.

Caiano directed the usual scenes with enough verve to make the standard stuff enjoyable and the performances agreeable. Assisting in making this film-going experience pleasant were some new and attractive faces, especially Daniele de Metz, and some fondly remembered veteran performers, including Barnes, Mario Petri, Folco Lulli of IL RATTO DELLA SABINE, Piero Lulli, and Gigi Bonos.

(Thank you to Wolfgang Meise and Ally Lamaj for helping me to see this in German, and George Badal for helping me to see this in French.)

Friday, September 18, 2009

The Battles of THE CASTILIAN

From: SO YOU WANT TO MAKE MOVIES

From: SO YOU WANT TO MAKE MOVIESMy Life As An Independent Film Producer

by Sidney Pink

We managed to finish principal photography on time, but we were left with a tremendous number of action and battle scenes to be shot. The only scene of major importance Seto had been able to film was the climactic final battle at Hazinas. We used the actual site of that historic battle and filmed it exactly as the tales of Jerifan related it.

History tells of the Moorish battle strategy of forming their huge armies into a giant crescent composed of their well-armed infantry. The first attack was led by the cavalry, which was reputed to be the finest and most ferocious in the world. After the cavalry herded the opposing forces into a circle of defense, the main infantry attacked in that fearsome crescent which, like a nutcracker, could close around the defensive circle and annihilate the enemy troops, leaving them no escape. This tactic expunged all opposition without any defeats, but Fernan Gonzales found a way to defeat the crescent.

In our final battle, we re-enacted the exact (according to legend and history) battle and tactics involved. Fernan aligned all of his troops in the form of a cross, with the arms reaching almost all the way across the valley. The main body of the cross was a half-mile long file of foot soldiers, twenty abreast, and at the rear of the column was the Castilian cavalry. His plan called for this cross to march toward the Moorish troops; when the cavalry of the Moors attacked, the foot soldiers parted and allowed the Moors to go through. At this point, the Castilian cavalry turned tail and ran, leading the Moors into a small valley where they were ambushed and decimated by expert Castilian archers.

Meanwhile the Castilian cavalry returned to the scene of the battle. The crescent of the Moorish infantry was unable to bend the arms of the Castilian cross to encircle their forces. After a short battle in which the Moors were unable to accomplish what they had been trained to do, they broke and ran, with the Castilian cavalry in full pursuit. Of course, legend had embellished this defeat with all kinds of supernatural help, including visits to earth by Spanish patron saints brandishing swords of fire, but this did not diminish the obvious military genius of the backwater Spanish hero Gonzales. This battle set the high-water mark for the Moorish invasion, but the Moors never got any further. It remains a remarkable achievement.~Our shooting plan called for us to establish the shots with four cameras (again my TV training stood me in good stead) located on two hilltops that commanded a view of the entire valley. Two of the cameras had long focal-length lenses for a master shot encompassing the entire length and breadth of the valley. Their field of vision included all the Moorish troops, numbering 5,000 on foot and 765 horses and cavalry. They were formed in the crescent, with the horses and riders moving across the front of the crescent of infantry.

It was one helluva sight. We had to keep the horses in motion, because most were untrained gypsy plow and work animals who were almost impossible to keep in any kind of order. It took us three days of rehearsals to get those raw extras to obey our commands. Our Castilians numbered 1,300 infantry and 300 cavalry, and it took us five days of rehearsal to get them disciplined enough to form a cross and keep it for the ten minutes required to get the shot. We were finally able to get the two cameras with the deep optical lenses positioned to portray the entire panorama of these two giant armies marching to the attack.

The other two cameras with shorter focal-length lenses were placed where they could pick up much closer shots of the action of smaller groups. This was about all we could do with such a mass of humanity. We decided that after we finished with principal photography of the picture, we would pick up all the close action between the heroes and the villains as well as the specialty action of our stunt men. This proved to be the best and least expensive solution. As I later learned from Al Wyatt and Yakima Canutt, the directing of action and stunt scenes is a highly specialized and difficult job. They should know, they were the greatest at it.

We were finally able to get that big scene on film. It took a total of three weeks of planning, hundreds of thousands of pesetas, and grand-scale preparation for moving, feeding, and housing almost 10,000 people and animals. The final result is approximately five minutes of film. It is spectacular, but I never want to do that again. Perhaps DeMille or Bronston with unlimited budgets and expert technicians enjoyed this kind of filming, but not me. Never again.

Thursday, September 17, 2009

DUELL VOR SONNENUNTERGANG

DUELL VOR SONNENUNTERGANG

DUELL VOR SONNENUNTERGANGU.S.: DUEL AT SUNDOWN

Director - Leopold Lahola 1965

Cast: Peter van Eyck (Don McGow), Carole Gray (Nancy), Wolfgang Kieling (Punch), Mario Girotti (Larry McGow), Todd Martin, Giacomo Rossi Stuart,Deineler Bitenc, Kurt Heintel, Jan Hendriks, Carl Lange, and Walter Barnes (Vater McGow).

Screenplay by Leopold Lahola, Anya CorvinBased on an idea by Inarek Blasko and Leopold LaholaDirector of Photography Janez KalisnikMusic by Zui BorodoAssistant Director Dragoljuh SlojanovicScmilt Wolfgang WehrumProduction Manager Willy ZeynDesamlletung Dr. Alexander GruterA production of Corona Filmproduklion G.M.B.H. Munich And of Eichberg G.M.B.H. MunichIn collaboration with Jadran Film, ZagrebDistributed by Omnia Deustche Film – Export G.M.B.H.

If someone wanted proof that all Westerns made by Germans weren't like the Winnetou films, this movie would do the trick. Unfortunately, what this movie was wasn't good.

Older son Don McGow was put in charge of the cattle drive. However, an argument with his younger brother, Larry, sent Don away to cool off. Returning, Don found the cattle stolen, the foreman dead, and Larry missing. Soon, our hero set off to discover where was the herd and what had happened to his brother.

With a plot that promised alot of action and emotion, this film delivered a listless pace and absolutely no involvement. At time the actors seem to have been directed to not react to what was going on around them, making audience identification difficult at best. And what little action was presented, was so poorly staged that one couldn’t help but wonder what the filmmakers thought they were achieving.

Fans of German actor Peter van Eyck would probably be astonished to find out that he played the hero of a Western, and from his performance here, it would appear that he wasn't very comfortable with the idea either. Aside from an overdone costume - which included chaps, an unweathered vest, huge gloves and a black hat which flapped in the wind - van Eyck didn't look healthy, let alone virile enough to work as a cowboy. His usual aristocratic manner, which perfectly suited the military and espionage parts he often played, seemed at odds with the rough character needed for this story. And having him next to Walter Barnes made the concept of van Eyck being a son very unconvincing.

In reality, Peter van Eyck was born in 1911, about seven years before the 1918 birth of Walter Barnes. Van Eyck died in 1969, about four years after this movie, but not before making at least fourteen other films, including THE SPY WHO CAME IN FROM THE COLD and SHALAKO.

As the ranch owner, Barnes provided sincerity for the part of a father worried about how his sons were growing up. The filmmakers didn't provide much for the actor to do, but he provided what little credibility their movie had.

In an attempt to make Barnes believable as van Eyck’s father, the filmmakers added gray to his hair and beard, and had him walk with a limp. Unfortunately, the American looked like he was trying to play older, which only focused more attention on how healthy and virile he appeared next to van Eyck.

Italian actor Giacomo Rossi Stuart, already a veteran of a few Italian Westerns, appeared in the small role of the foreman. That the producers wanted to add him to the mostly German and Yugoslavian cast was odd, especially as they didn't give him much to do. But his was always a welcome presence.

Probably the most interesting element of this film was the actor playing Larry McDow; Mario Girotti. This was one of five German Westerns in which this fellow appeared. Two years later, he would dye his hair blonde, adopt the name of Terence Hill, and become a big star in Italian made Westerns. Here, he showed a little of his star quality with his brilliant smile and casual athleticism - he vaulted over fences and onto horses with ease. However, the role of Larry was not the sort of part to bring him to the attention of a very wide audience. But, at least, it didn't prevent him from going on to bigger and better things.

(Thank you to Ally Lamaj for helping me to see the German language version of this.)

Wednesday, September 16, 2009

An editor for THE CASTILIAN

From: SO YOU WANT TO MAKE MOVIES

From: SO YOU WANT TO MAKE MOVIESMy Life As An Independent Film Producer

by Sidney Pink

Seto hadn't the vaguest idea how to stage or photograph a battle scene. Every attempt he made ended in disaster and we soon gave up, realizing we would have to save all of those scenes until the end of our schedule. Originally, our film editor was a French woman in her sixties who went by the affectionate name of Senora Madame. She was a very capable cutter and her technique was good enough for any Spanish film, but like Seto, she was in over her head when it came to our picture. We needed a film editor with the ability to edit battle scenes and create the faster tempo needed for international audiences.

Let me illustrate what I mean by tempo. In European productions, customary cutting called for, say, an actor to walk down a hall, open the door, enter and close the door; and then for the cut inside the room matching the door closing to show him actually inside the room. This kind of cutting slows action too much for American audiences, who are accustomed to being told a complete story in a thirty-second commercial. American cutters show this same sequence of events by following the actor into the hall, cut to a close-up of the door, and then show the actor talking to whoever he went to see. Our audiences do not need a complete explanation to accept the fact and the process of the actor entering the room.

I was having a real problem explaining to Senora Madame Ochoa we could not accept her Spanish-French cutting technique and had to use a different approach. While I was in the States, I met a film editor recommended to me by Eddie Mann and Freddie Berger. His name was Richard Meyers and he was eager to get to Europe. At this time almost all the production activity worldwide was in either Rome or Madrid. Spain had taken over as a center due to its excellent climate and terrain. You could find any outdoor background in Spain, from the frozen Russia of DR. ZHIVAGO to the deserts of LAWRENCE OF ARABIA.

At any rate, Rich was very ambitious, not content to remain an excellent film editor. He had his heart set on becoming a producer-director. He was, however, amenable to the deal I offered, and he came to Madrid with his family to take over as associate producer and supervising editor of the picture. Again the unreal importance of titles in this crazy showbiz world worked for me. Rich was content because he was not merely a film editor, and Madame was happy because she was still officially the only editor on the film. Nothing changed - each had the same job, but they were both content because they saved their faces through titles.

With Rich in charge, we were able to keep Seto in touch with his coverage, and thanks to his able cutting and production savvy we had very few problems in that department. Now I was able to concentrate on the other miseries in progress.

Espartaco determined that no matter what the cost he would even the score with me, and he caused furor after furor until Emiliano Piedra re-entered the scene. He came as the representative of a now wide-awake Maruja Diaz. When she saw the assets of her company squandered by the obstinacy of the man who had posed as her husband (we learned they had never been married), she called upon Emiliano, who was scrupulously honest and Maruja's best friend.

On her behalf, he quickly executed an agreement with us for our guarantee of completion in exchange for production control. Under Spanish law, final control resided in the Spanish co-producer. What Maruja needed was assurance that Espartaco, who was not a Spanish national, could not in any way conspire with us to defraud her of her company and its share of the film. After seeing the results of the enmity between us (we were not two weeks behind), Emiliano advised her to turn over production control to us legally and thus blunt any power held by her ex-partner. And that was the way we finished the picture. Espartaco was now only an actor, and we were able to control him.

Tuesday, September 15, 2009

Followup on Eli and Federico

Tullio Pinelli, left, who co-wrote the film "La Strada" with Federico Fellini, far right, is seen in 1957 with the film's co-producer, Dino de Laurentiis, and star, Guilietta Masina. "La Strada" won the first ever Academy Award for best foreign-language film. (Los Angeles Times)

Tullio Pinelli, left, who co-wrote the film "La Strada" with Federico Fellini, far right, is seen in 1957 with the film's co-producer, Dino de Laurentiis, and star, Guilietta Masina. "La Strada" won the first ever Academy Award for best foreign-language film. (Los Angeles Times)From: DINO The Life and Films of Dino De Laurentiis

by Tullio Kezich and Alessandra Levantesi,

translated from the Italian by James Marcus

(In an excerpt from Eli Wallach's autobiography, the American actor talked about meeting Federico Fellini and being offered a role in a movie to be produced by Dino De Laurentiis. Federico backed out of making the movie, which led to lawsuits by De Laurentiis because of the amount of pre-production money already spent. Here's what is said about that project in the official De Laurentiis' biography.)

Then, in January 1964, as Fellini was preparing to shoot JULIET OF THE SPIRITS, Dino learned that his old friend was squabbling with his erstwhile patron, producer Angelo Rizzoli. Could it be time for a rapproachement? After some amiable discussions, Dino and Fellini signed an unusual contract, dated February 13. According to this document, they would make JULIET OF THE SPIRITS together is Rizzoli declined it, or as an alternative, a film "of a modern kind, i.e. without any costumes." There was also an option for a second film. Alerted to the situation, Rizzoli grew alarmed and accused Federico of wanting to betray him "with that Neapolitan down there."

In the end, JULIET was the last project Fellini would direct for the elderly Angelo. That left the second film. The contract between the old friends had specified an appropriate title, WHAT MAD UNIVERSE, a science-fiction novel Fellini had asked Dino to option. By now, however, the director had something quite different in mind, which he didn't initially share with his partner. This was a short novel by Dino Buzzati called LO STRANO VIAGGIO (THE STRANGE VOYAGE), which he'd read in a magazine eighteen years before: the story of a young man who mysteriously finds himself in the afterworld.

Traveling up to Milan, Federico invited Buzzati to knock out the screenplay with him. And so IL VIAGGIO DI G. MASTORNA (THE VOYAGE OF G. MASTORNA) came into being - amidst many doubts on Dino's part. The producer was less than enthusiastic about filming the other-worldly travels of a dead man. Throughout 1965, while Buzzati moved forward with the script, Fellini and Dino's brothers, Luigi and Alfredo, scouted locations in Naples, Milan, and Cologne. In the new studio at Dinocitta - where the director felt uncomfortable from the very first day, calling it "a space station, in inaccessible outpost" - various sets began to tape shape. These included a scale model of the Cologne cathedral and the airplane in which the cellist Giuseppe Mastorna believes himself to be landing safely. (Instead, the plane crashes, and the protagonist crosses over to the kingdom of the dead.)

Other pieces of scenery were hammered together, among them a Neapolitan set at Vasca Navale, and Dino procured hundreds of costumes. But now Fellini revealed an alarming listlessness. The maestro was in fact experiencing the crsis that he'd depicted earlier in 8 1/2; he was a director about to embark on a film he no longer wanted to make. He had come to believe that MASTORNA was bringing him bad luck - that messing around with the afterlife was not a smart thing to do. On September 14, 1966, Fellini had the following message delivered to his producer: "I must tell you that I've been debating within myself for some time, and that I've finally come to a conclusion... I can't begin the film because, despite everything that's happened, I wouldn't be able to complete it.... I'm so sorry, caro Dino, to have arrived at this decision, but it's the only thing I can do."

A war between the two friends exploded, with the newspapers fanning the flames. Dino filed a claim for 1 billion lira in damages; the court granted him 350 million and a bailiff showed up at the villa Federico shared with Giulietta Masina to begin the seizure of property. Since the attached goods added up to a smaller sum than the grant by the court, Dino also asked for the seizure of any funds still owed to Fellini by Rizzoli.

The skirmish was interrupted by the official premiere of THE BIBLE at San Carlo di Napoli. Meanwhile Luigi and Alfredo De Laurentiis did everything they could do to broker a truce between the director and producer. Fellini had made the situation worse by declaring that he was ready to make the film for a different producer. In fact, he may already have been in the midst of secret negotiations, but the intermediaries kept trying to cobble something together.

Finally Dino and Federico agreed to meet one evening in January 1967, in the park surrounding the Villa Borghese in Rome. When the appointed time arrived, the producer joined the director and his lawyer in their car. The trio circled the park slowly, over and over, with Dino's car and driver following. After an hour, the first car came to a halt, the occupants climbed out, and the two enemies exchanged a peacemaking embrace. All around them, meanwhile, retainers from both sides, who had been squatting on the grass, leaped forward in jubilation.

Since Fellini no longer wanted to work at Dinocitta, preparations for the film recommenced in the old studios at Vasca Navale. There was some thought of signing up Mastroianni for the lead role, but he was unavailable in April or May, when the shoot was scheduled to begin. It was also too late to hire an American star, so Fellini settled on Ugo Tognazzi. On March 13 he sent Dino a cheerleading note: "I've decided to use Tognazzi. Godspeed and good luck to us all" The actor, who hadn't yet made his break into real stardom, was overjoyed at the news and ran off to telephone his father. But on the evening of April 10, at a decisively unfavorable juncture, the director was rushed to the hospital with severe chest pains.

Dino couldn't believe it. Suspecting Fellini of faking illness to get out of making the film, he sent down his own team of doctors to the Salvator Mundi Clinic. But when the physicians returned with a catastrophic diagnosis - possible cancer - De Laurentiis was unable to hold back his tears. Luckily the next day examinations put these fears to rest. Federico was suffering from pleurisy, an infalmmation of the membrane separating the lungs from the abdomen, with complications from anaphylactic shock. The doctors prescribed a long convalescence, which had just begun when Dino himself had to be rushed to the hospital after an attack of appendicitis.

Did all this put MASTORNA on hold? Of course not. The recuperating director soon received a visit from Paul Newman. He'd been sent by Dino, who hoped that the maestro would cast him as Mastorna in place of Tognazzi - who, unjustly dropped from the project, ended up suing everybody.

In May the convalescent Fellini told one interviewer regarding Dino, "There's no longer any acrimony between us. On the contrary, I believe that Dino has a great deal of regard for me." It wasn't clear, however,whether the director still wanted to make the film of if he intended to make it with somebody else. As pragmatic as ever - and perhaps equally disenchanted by a project that had brought him such grief - Dino ended the suspense by relieving the director of his obligations. In return, on August 21, Fellini signed a contract to make three films with De Laurentiis over the next five years. He would never make a single one.

By now, the padrone of Dinocitta had lost all hope of breaking even on the project. Another Neapolitan producer, Alberto Grimaldi, nonetheless expressed interest in acquiring the rights to MASTORNA and reimbursing all of Dino's expenses. On September 25 Grimaldi presented Dino with a check and brought the entire dispute to an end. Fellini recounts the grand finale in this way: "Dino fell to his knees, shouting, 'San Gennaro exists, he's right here in front of me, his name is Alberto Grimaldi!" Today Dino dismisses this little scene as more fruit of the director's imagination, but he does say, "Not even this new San Gennaro could pull off what would have been a real miracle: convincing Fellini to make the film."

(Fellini would make SATRYICON and CASANOVA for Grimaldi instead.)

Monday, September 14, 2009

Cesar and Espartaco during THE CASTILIAN

From: SO YOU WANT TO MAKE MOVIES

From: SO YOU WANT TO MAKE MOVIESMy Life As An Independent Film Producer

by Sidney Pink

These were only a few of the early problems that plagued us in our nineteen weeks of principal photography. VALLEY was the most difficult picture I worked on, but I learned what not to do, and the project had its compensations as well. Cesar Romero was a real delight. He is a gentle and intelligent man, and we spent many evenings together in quiet conversation over coffee and the fine Spanish brandy. He talked about his early days in the actor pool of 20th Century Fox with Tyrone Power, Don Ameche, Betty Grable, Alice Faye, and Rory Calhoun. I shall always like Cesar Romero, and in fact, he is one of the most loved and respected actors in Hollywood. It was he who got me to grow the first and only beard I have ever worn. The part of Jeronimo called for a full beard, so I suggested he grow a real beard to avoid the dawn makeup calls. He reluctantly agreed but only if I also grew one. I did so, and for those twelve weeks I wore it, I was miserable. As the weather warmed up and the beard grew longer, the discomfort increased, and we were both soon counting the days until the damned things could come off. I had the last laugh on him because he received an offer to co-star with John Wayne in DONOVAN'S REEF immediately after completing VALLEY, but he had to keep his beard, this time trimmed to an elegant Vandyke.

Cesar was loved in Spain, but unlike in other countries, his fans there never approached him for autographs nor did they molest him in any way. They just followed him wherever he went. He was quite a sight with his beautiful flowing white hair and magnificent beard, walking along the streets and dwarfing everything and everyone in sight. I am nearly six feet in height, but somehow I looked small when I was with Cesar. Those evening walks were a genuine pleasure for me after my daily battles with Espartaco.

I took a vow I would never again get involved with anyone like Espartaco Santoni. After the first few weeks of insecurity, when he allowed us to carry the ball and organized the confusion, his ego mounted daily with the knowledge the picture was back on schedule and moving well. He finally scored with Tere Velasquez, but his nightly visits with her did not make him any easier to live with. Even vainer that she, he constantly demanded our makeup woman between every scene; he carried a mirror with him to check his hair and make sure of his beauty.

He became one giant pain, but when he began to throw his weight about by abusing Cesar Romeo, all of the crew lost respect for him. To show his power, he ordered Cesar to be on the set every day even when he wasn't scheduled. During all of this Cesar remained his usual quiest and patient self, sitting quietly reading a book of talking with me. His forbearance soon won him the title of San (Saint) Cesar from the crew, and their dislike for Espartaco grew daily.

The stuff hit the fan when Espartaco decided he would not accept the lines of Jeronimo read by the script girl; he insisted they be read by Cesar personally. No one ever asked that of another actor unless the lines were needed for timing of were to be used in a direct soundtrack. It was like deliberately degrading that fine professional in front of the whole crew. When Cesar got up to do as requested, I blew my stack.

I had kept my cool because of Cesar, who refused to let it bother him. But now I told Espartaco in my best four-letter-word Spanish what I thought of him. I indicated that Cesar Romero and I, together with all of the American production team, were walking off the set. We would not return until he made a public apology in front of the whole crew, and we were prepared to take him to court to make certain the picture would never see the light of day. When I finished, there was a burst of spontaneous applause that must have reduced Espartaco to the pygmy he was. An hour later we were back on the set to receive his ill-given apology. From that day on, Espartaco Santoni and I shared a mutual hatred.

Luckily for us, Espartaco had no scenes with Frankie Avalon so he never even met him. Frankie's scenes turned out exceedingly well; Seto was content to let us control the way Frankie was presented. Espartaco had only one scene with Valli, and she treated him as if he wasn't there. He was on his best behavior with Tere, and he treated her as he would a real queen. By now his affair with Tere was public knowledge, even to Maruja. She appeared on the set for a weekend in Burgos but left a few hours later in tears.

Espartaco married Tere Velasquez after destroying Maruja, but that too had only a brief life. They had a child, but Tere could not stand his lies and infidelities, so she booted him out and went back to Mexico. I still can't understand what it is about showbiz that tolerates these kinds of parasites for as long as it does.

Sunday, September 13, 2009

WINNETOU 1. TEIL

WINNETOU I.TEIL

WINNETOU I.TEILYugoslavia: VINETU 1

Italy: LA VALLE DEI LUNGHI COLTELLI

France: LA REVOLTE DES INDIENS APACHES

U.K.: WINNETOU THE WARRIOR

U.S.: APACHE GOLD

Director - Harald Reinl 1963

Cast: Lex Barker (Old Shatterhand), Pierre Brice (Winnetou), Mario Adorf (Frederic Santer), Marie Versini (Nscho-tschi), Walter Barnes (Bill Jones), Ralf Wolter (Sam Hawkins), Mavid Popovic (Intschu-tschuna), Branko Spoljar (Bancroft), Niksa Stefanini, Dunja Rajter (Belle), and Chris Howland (Jefferson Tufftuff).Husein Cokic, Demeter Bitenc, Vlado Krustulovic, Ilija Ivezic, Teddy Sotosek, Tomoslav Erak (Tangua), Hrvoje Evob (Klekih-petra), Antun Nolis, Vladimir Bosnjak, Kranjcec Ana.

Screenplay by Harald. G. Petersson

Based on the novel by Karl May

Director of Photography Ernst W. Kalinke

Cinemascope - Eastmancolor

Music by Martin Bottcher

Art Directors Frank Goslar, Dusko Ercegouic

Editor Hermann Haller

Production Manager Erwin Gitt

Second Unit Producer Josef Lulic

Second Unit Director Stipe Delic

Second Unit Camera Kreso Grcevic

Camera Eberhard Dycke, Egon Haedler, Milorad Markovic

Costumes Irms Pauli

Sound Editor Fedor Jeler

Make-up Walter Wegner, Gerda Wegner

Special Effects Erwin Lange

Bauten Vladimer Tadej

Assistant Director Charles Wakefield, Slavko Andres

Executive Producer Horst Wendlandt

Interiors CCC - Studios Berlin

A Co-production of Rialto Film (Hamburg), Ste Nlle de Cinema (Paris), and Jardan Film (Zagreb).

Actually the second of the series, WINNETOU 1. TEIL came out almost a year after DER SCHATZ IM SILBERSEE (U.S.: THE TREASURE OF SILVER LAKE), but was for many fans the best of the German Westerns.

What made this film special in the Winnetou series, was that it was the "origin" episode. Here, we saw how the future chief of the Apaches, and the White man who would become his blood brother, first met, and the physical trials which forged their bond.

Since the politicization of the cinematic presentation of Native American peoples, it was hard to see any movie about Indians without wondering, "What would Russell Means think about this?" How authentic was the film's depiction of the Mescalero Apache? Was the language used by the cinematic Indians correct? Did the costuming approximate how they really looked? Would these people really build their pueblo on a cliff overlooking a river valley? Such questions would probably be more appropriately posed to anthropological or historical scholars, and these scholars would probably point out that this film's portrayal of the characters from an European background wasn't authentic either. But, the filmmakers were not attempting a realistic study of the subject. They were presenting an adventure story which romanticized the Western expansion of the United States. In particular, they were portraying an idealized friendship between a Native American leader and an European American railroad surveyor, who happened to be good with his fists.

Action seemed to be the most important aspect of this project to the filmmakers, and they provided quite a few well-staged and well-produced sequences. There was the wagon train racing across the prairie pursued by the murderous Kiowa. There was the saloon punch-up after which Sam Hawkins christened the surveyor "Old Shatterhand". There was the battle of Roswell, during which the railroad workers attempted to arrest Santer for the murder of

the old White teacher who lived with the Apaches. And there was the attack on Roswell by the Apaches.

the old White teacher who lived with the Apaches. And there was the attack on Roswell by the Apaches.

Unfortunately, among the action sequences were a number of preposterous bits. Particularly hard to swallow was the idea that workers could lay railroad tracks at night leading right up to the saloon without anyone in the saloon knowing about it. Also not quite convincing was that the villains trapped in the saloon, could, just overnight, build an underground tunnel through the floor of the drinking establishment across to a storehouse filled with dynamite.

Underground tunnels were an element unusual to American Westerns, but seemed okay to these German filmmakers. In DER SCHATZ IM SILBERSEE, a frontier stockade had a secret passageway down the well, which came out quite a distance outside the fort. However, in both films, the interior of the tunnels were never shown, so questions were never answered about their contruction.

Another unusual element found in the Winnetou Westerns was "trial by ordeal", which was very similar to the "feat of strength" found in Italian Epic films, and, of course, was a common element of most mythological tales. In DER SCHATZ IM SILBERSEE, Old Shatterhand had to prove his innocence by defeating an Indian chief in a duel using tomahawk and knife while both were tied around the waist with rope also attached to a totem pole. In WINNETOU 1. TEIL, Old Shatterhand must prove his innocence by reaching a totem pole in a leaky canoe while being

pursued by Winnetou's father.

pursued by Winnetou's father.

As Bill Jones, Walter Barnes continued the trend, started with DRAKUT IL VENDICATORE, of getting roles with more stature than his earlier parts. The foreman of the railroad builders, Jones was a well-meaning man unaware that Santer had altered the proposed route of the track. Instead of going around Apache land, the track was now going right-through the heart of it, providing a cost saving that Santer was pocketing.

Later, after Santer and his men took cover in the saloon to avoid capture, Jones ventured out unarmed in an effort to halt the bloodshed. His effort to convince the villain to lay down his weapons was, not surprisingly, rewarded with a bullet. But the effort signified that Jones was a character of heroic virtue, and Barnes filled the role admirably.

However, the roles which really made WINNETOU 1.TEIL a success were those filled by American actor Lex Barker, as Old Shatterhand, and French actor Pierre Brice, as Winnetou. The roles were written in the style of classical heroes, and needed performers with strong physical charisma to pull them off. In Barker and Brice, the filmmakers got what they needed. Ralf Wolter as Sam Hawkins was a regular of the Winnetou films which featured Old Shatterhand, appearing in six out of seven; he wasn't in WINNETOU 2. TEIL. A comedic character, Hawkins was the old-timer who helped introduce Old Shatterhand to Winnetou, and was a good fighter in addition to providing humor. WINNETOU 1. TEIL did not include the moments from DER SCHATZ IM SILBERSEE which revealed that his eccentric hairstyle was actually a wig, to cover up his bald spot.

Following Herbert Lom's stint as the villain in the first of the series, German actor Mario Adorf brought to the film the forceful presence which made him an international star. As Santer, Adorf seemed to be at home in Western garb, which probably helped to convince American director Sam Peckinpah to cast him, a few years later, in MAJOR DUNDEE.

Casting Marie Versini as Winnetou's sister Nscho-tschi seemed appropriate; who better than a French actress to play the sister of a character played by a French actor? Versini brought sweetness to the role which was just about all the script allowed. Viewers of WINNETOU 1. TEIL may have been surprised to discover Versini also played Nscho-tschi in 1966's WINNETOU UND SEIN FREUND OLD FIREHAND (U.S.: THUNDER AT THE BORDER). However, Old Firehand was part of Winnetou's life before he met Old Shatterhand, so this story was kind of a prequel to the events of WINNETOU 1. TEIL.

All of the Winnetou movies used the same music by Martin Bottcher, which gave them a continuity, but also signaled the filmmakers unwillingness to change with audience tastes. The last installment of the series was released in 1968.

Saturday, September 12, 2009

Bernie Glasser To The Rescue of THE CASTILIAN

From: SO YOU WANT TO MAKE MOVIES

From: SO YOU WANT TO MAKE MOVIESMy Life As An Independent Film Producer

by Sidney Pink

Actually, our major problem turned out to be lack of an experienced cutter and a producer who understood the requirements of this major production effort. No one at MD had the experience to comprehend the magnitude of preparation needed to make a giant film like VALLEY. The production demands we faced were akin to planning a giant military operation. The confusion lasted several days, until I took matters into my own hands and approached Espartaco. I made it clear that unless he was able to get the right production crew, we were lost and I was ready to pull out. We held a production conference, and I suggested we hire one of the American production managers from the Bronston company, whatever he might cost. Espartaco agreed.

We were able to get one of Bronston's key production unit managers on a lend-lease agreement. Bernie Glasser joined us in a few days, and he was worth every dime we paid him. In short order he organized all of the production personnel into teams, each one charged with a specific function. We had to feed thousands of extras on location, who, since they were needed all day, had very little time to spare for lunch or dinner breaks. Bernie was able to get the cook tents and tables so arranged that one day we fed 11,000 people in three hours. The rounding up of so many horses, equipment, and people into the hinterlands around Burgos necessitated dragging people from fifty miles away, while the horses had to be transported from all over northern Spain. We used railroad cars, vans, buses, and anything that moved when we got to those scenes. Bernie prepared everything so well in advance that almost everything went off smoothly.

The only hitches came when his carefully structured orders were not complied with literally. He then turned his attention to Seto and Pacheco, with whom he had some rather violent sessions. Seto realized his entire future rode on the outcome of VALLEY, so he agreed to follow Bernie's suggestions. He learned to preplan every scene and every camera move and to rely on Bernie's production expertise.

Pacheco, on the other hand, took it like the bantam rooster he resembled. He didn't like Bernie and he made not bones about it. His Spanish pride was being challenged by an upstart American, and he was not about to take advice from some damned gringo who had never turned a camera in his life. Mario was a superb cameraman and the stuff he had shot was spectacular, but he was spending too much time arguing with Seto and trying to get perfect lighting on every scene. We were six days behind in our first fifteen days of shooting and we could not afford temperamental fits.